Understand intensity domains to simplify your training thresholds (Part 2)

By Scott K. Ferguson, Ph.D. | Co-Founder and Head Coach

Dr. Ferguson undergoes some exercise testing in the laboratory at the University of Exeter (Photo credit: Abigail Ferguson)

Humans like to itemize events to help simplify our understanding of complex processes, and this is no different when it comes to exercise training and endurance performance. Over time, we have developed thresholds to help explain the complex phenomena that occur as we go from rest to maximal exercise. Unfortunately, the development and use of thresholds in endurance training has become quite complex and often leads to confusion, even among those who have formally studied exercise science.

Have a look for yourself! Google "endurance training thresholds" and you'll get 8,780,000 results with the top snippet showing seven different endurance training zones!

It's easy to find articles espousing the importance of each of the seven thresholds; however, after reading the literature and discussing the issue with colleagues and fellow coaches, its become clear to me that most elite endurance athletes and coaches focus only on three distinct intensity zones, separated by two thresholds...yes only two thresholds. In this post, we will build on our previous article on lactate and identify what these two important thresholds are to help you understand our approach to endurance training. Our third and final article will bring our discussion around full circle and explain how elite athletes use these thresholds in their training and how we use them to guide our clients.

If you haven't read our previous article on lactate, you'll want to check it out first as we dispel the dogma that lactate is a bad thing that causes muscle soreness. For many athletes, the lactate threshold (LT) is a term used to describe the unsustainable accumulation of blood lactate. This threshold lies very close to the maximal sustainable exercise intensity for a given athlete and thus has been utilized as a proxy of endurance exercise performance. Described this way, it’s very clear as to why we would want to know and raise our lactate threshold; the higher intensity/speed we can sustain for a given time, the greater distance we can cover. However, a thorough search of the academic literature can leave many confused as to what exactly the lactate threshold is, where it lies with regards to exercise intensity and how it differs from the many other terms used to describe similar physiological events. So, let’s lay out some of the many terms used within the literature to describe the maximal sustainable exercise intensity for an athlete:

Aerobic Threshold (AeT): This is a relatively low-intensity exercise work rate; one that could easily be sustained for several hours. From a physiological perspective, the AeT marks the point at which blood lactate increases above resting values. Some coaches refer to the AeT as the first lactate threshold and elite endurance athletes spend the majority (over 70%) of their training time at or below this threshold.

Lactate Threshold (LT): As mentioned above, many consider the LT to be the point above which blood lactate levels can no longer be sustained at a steady-state, but instead rises until the intensity of exercise is reduced. I too considered this the case until I began noticing many well-established basic and applied physiologists reporting otherwise. For example, Professor Andrew M. Jones, who worked with marathon record holder Paula Radcliffe, has referred to the LT as the point at which blood lactate rises above resting values but does not increase over time. This occurs during the transition between the moderate and heavy exercise domains (we will talk further about these domains in a future article) and is what many refer to as the Aerobic Threshold.

Maximum Lactate Steady State (MLSS): The MLSS, is the highest-exercise intensity at which blood lactate concentration (and oxygen uptake, VO2) can be stabilized during sustained-exercise. Sounds an awful lot like what we thought the LT was right? An article written by Iñigo San Millán, PhD for Training Peaks suggests the same thing. However, the data suggest that the maximal sustainable exercise intensity for an athlete lies just a bit beyond this MLSS. What shall we call this threshold?

Critical Velocity/Power (CV/P): This could be considered the “Holy Grail” of thresholds. While the critical power does not refer exclusively to blood lactate concentration, it does describe the maximal rate of exercise that can be sustained for a prolonged amount of time above which a sustained decay of physiological function occurs. More specifically, the CV/P is very closely related to the MLSS in that as soon as exercise intensity (defined as power or speed) is increased above this threshold we see a rapid increase in blood lactate, oxygen uptake (until VO2max is achieved), and many fatigue associated metabolites…that’s right, a whole heap of fatigue associated metabolites (not just lactate) begin to accumulate above the critical power. This is not the case for the MLSS or LT as explained above. For an excellent review on this topic written by experts in the field, see here. This really cool threshold actually holds true across exercise modalities (i.e. swimming, running and cycling) and even across species (mouse, rat, horse…even salamander)! The key point here is that this threshold separates sustainable exercise from the unsustainable intensity.

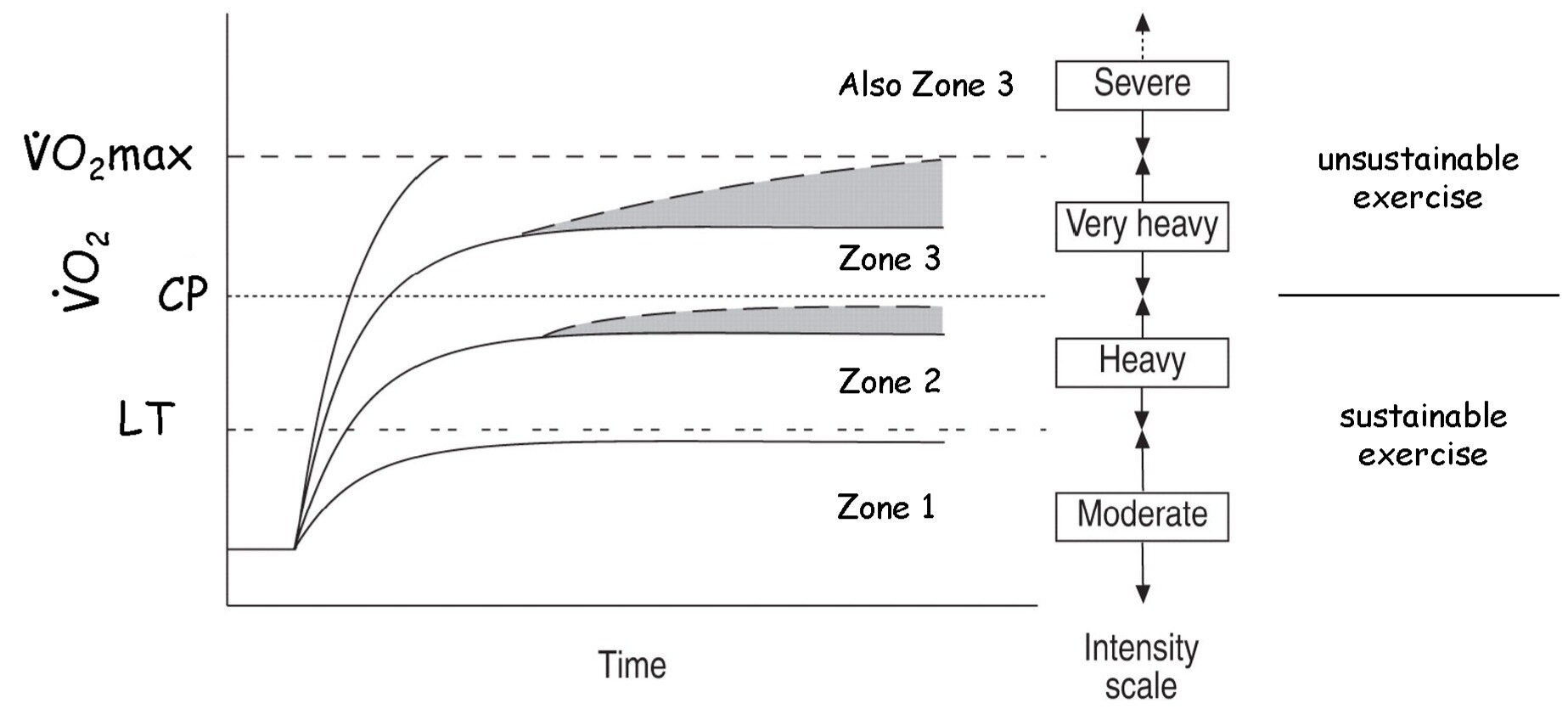

The figure below illustrates where the lactate threshold and critical power lie in regards to sustainable vs. unsustainable exercise and when applied, make the three distinct zones that we spoke about earlier. Zone 1 is very easy exercise that can be sustained for a long duration (think hiking over easy terrain with an unloaded pack). Once we cross the LT we enter zone 2, which is a challenging but sustainable and fun intensity of exercise. This intensity is usually where shorter distance endurance events (up to around a marathon) are completed. Finally, after we transition above the CP we enter zone 3, which is unsustainable for long durations. We will speak more on these three zones in our next discussion.

The takeaway

So what are the takeaways?

The lactate threshold and aerobic threshold are one and the same and separate easy (or moderate in the figure above) intensity from heavy intensity exercise.

The maximum lactate steady state (MLSS) although sometimes called the LT, lies very close to the critical power/speed. For the non-scientist, these two thresholds (MLSS and CP) can be considered the same and separate sustainable from unsustainable exercise intensity. When you exercise above critical power, you are on borrowed time and time to fatigue is calculable.

Hopefully, this article has helped identify three distinct exercise intensity zones and the two thresholds that separate these zones. Our next and final article in this series will further improve your understanding of these thresholds and shed light on how elite endurance athletes use them to inform their training.